Eye-rolling, defensive, distrustful of sincerity. The type that poo-poos the rhetoric of most MPs, runs a mile from anything to do with homeopathy and can see straight through when someone’s trying to sell you something. Could this very kind of cynicism be causing the world of content to create something altogether better?

I believe I have delightfully observed something in my mapping of today’s content trends. It’s a bubbling undercurrent that seems to have grown from an acknowledgement of our growing cynicism.

Now, generalisations are generally dangerous – and we should be, well, cynical of them. And while I can speak for myself in terms of how I like to be treated as a person first, and a consumer second, it’s always useful to look to the figures to add some heft to a hunch.

Correlating behaviours and characteristics, a study featured in Harvard Business Review in 2014 found that millenials were 11% less likely to say that people can be trusted, and following that trend, earlier this year Brand Quarterly published a feature exploring how generation Z is the most cynical so far. With all we’ve had to face over the last few years, can you blame them? There is a lot to be cynical about, whether its distrusting the establishment, seeing the bad behaviour of corporations, having their faith in social media challenged, or left to contend with batty politicians leading the most powerful countries in the world – the realisation that the powers that be are not always (and sometimes very rarely) right has changed the tune of young people. And of course, this plays out in the world around us. The belief that we ‘don’t have to take it anymore.’ That we can push back, shout out, march for change. In turn, brand content has a lot it needs to do to engage and connect with a generation that feels simultaneously disenfranchised and powerful .

So when it comes to branded content. We’ve wised up. We expect more.

It means that lazy, poorly produced branded content that’s quite clearly trying to sell us something while masquerading as something else, just won’t fly. Like some badly-placed native advertising that can feel awkward, flagrant and shoehorned in. The lazy magazine advertorial, that’s 90% product focused and 10% selling the virtues of boiled canned meat. The influencers ‘best buys’, or ‘top tips’, totally not sponsored (all completely sponsored).

Think about it, when was the last time you invested your time in reading poorly produced sponsored content in an advertorial magazine feature, and didn’t feel a bit sad about the world?

Let me back track. Branded content has become one of those charming buzzwords, that seems to elude any kind of definition. Even industry giants can’t seem to agree on what it is. In my humble opinion, it seems to suggest a piece of content; film, article, event, playlist, even a piece of poo (seriously), that’s associated with a brand, either in direct affiliation or background support.

Seeing through the ulterior motive.

It spans everything from native advertising – where adverts and sponsored content migrate into different platforms and publications to mimic the layout, look and style of where they’re being put, like content chameleons (think Onion articles sponsored by Spotify, Emerald Street newsletter drops about expensive eye creams) – to affiliated produced films, article features, and generally content produced with an ulterior motive.

“Native advertising at its worst can hoodwink readers into thinking commercial content is editorially independent."

When it comes to branded content (or brand content or content brand – the jury’s out on what to name it), we are readers, viewers, spectators and listeners first – and consumers second. And we’re looking for a better deal. That means the content we’re interacting with needs to offer us something of real, tangible, authentic value. And can’t sideline us by being opaque about the truth of the motive. The Guardian Labs’ Anna Watkins shares this sentiment, saying that “native advertising at its worst can hoodwink readers into thinking commercial content is editorially independent.”

It’s this evolution of the expected value, that’s seen huge shifts in how people are producing branded content.

To feed and foster loyal brand advocates, the content brands are creating needs to really speak to its people. And above all it needs to be good.

Telling better stories. Playing with new concepts and ideas. Giving the reader something of real value. To me, the best branded content is the kind that either makes me question the motives for even being involved at all, like this film made for Intel and W Hotels. Or a piece of content that actually tells me something I’m going to remember and enjoy, like these recipes that I regularly turn to on The Pool in conjunction with M&S.

Giving the reader more credit and something of value through branded content is not a new concept by any means.

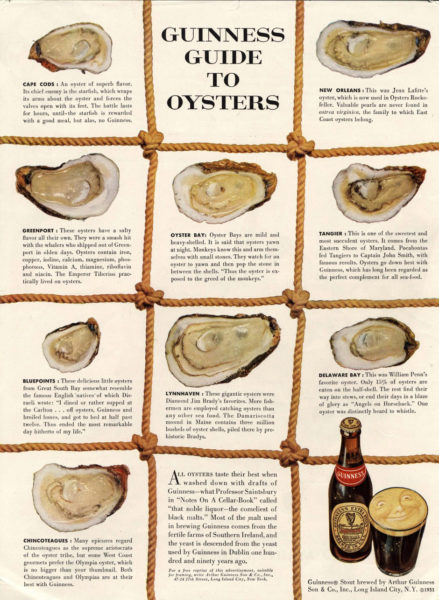

Just looking back to some of David Ogilvy’s first ever work in advertorials, shows that he grasped the concept of giving the reader something – like the Guinness advertorial feature on oysters, or this Rinso advertorial that housewives tore out of the magazine and kept in their laundry rooms.

More current examples include the ever inventive masters of branded content Red Bull’s Jason Paul Goes Back in Time, an octane-charged, captivating freerunning film that aces the art of a narrative driven story which is both on brand and authentic – consequently lapped up by audiences worldwide. Dove’s Real Beauty Sketches follows in the clear set tracks of the brand’s commitment to content campaigns that address body positivity for women, While Netflix partnership with the New York Times to create meaningful content that supports the release of the latest Orange is the New Black series shows the power of the right collaboration at the right time.

But doesn’t this mean we’re still being sold to, just in a more clever way?

Absolutely. And I applaud your cynicism. Better branded content that blurs the lines between traditional advertising and general content, means we’re simply being sold to in a different – and some might say – altogether more Orwellian way. But it also means that the content they’re producing is giving us, as viewers, readers and humans more credit, and has to have more creativity and craftmanship to it. There’s more value to it. More purpose. Entertain, engage, inform, sure, but also, motivate, encourage and sometimes even engender change for the better.

For brands, this means we’ll associate the creative visions, the intelligent concepts, the value of craftsmanship, and investment in production, with the brand’s overall integrity. With the idea at the heart of it.

"We'll associate the creative visions, the intelligent concepts, the value of craftsmanship, and investment in production, with the brand's overall integrity."

Because really, while brands and products are funding the operation, the fact that they’re essentially selling something – whether it’s their culture, thought-leadership or an actual product – makes it more of an afterthought; playing second fiddle to ruddy good content that we actually want to consume and share.

Which, if they’re going to be advertising anyway, is kind of a win-win situation for us as consumers.