The shadow of war hovered over us all. Sirens, alarms and the dull thud of ordnance finding its mark could still be heard on clear days and it was in part to block out this unwelcome punctuation that Henry Ayton conceived of a jazz workshop to be held on Saturday nights on board The Renown…

The Offshore Sessions, Wyl Menmuir

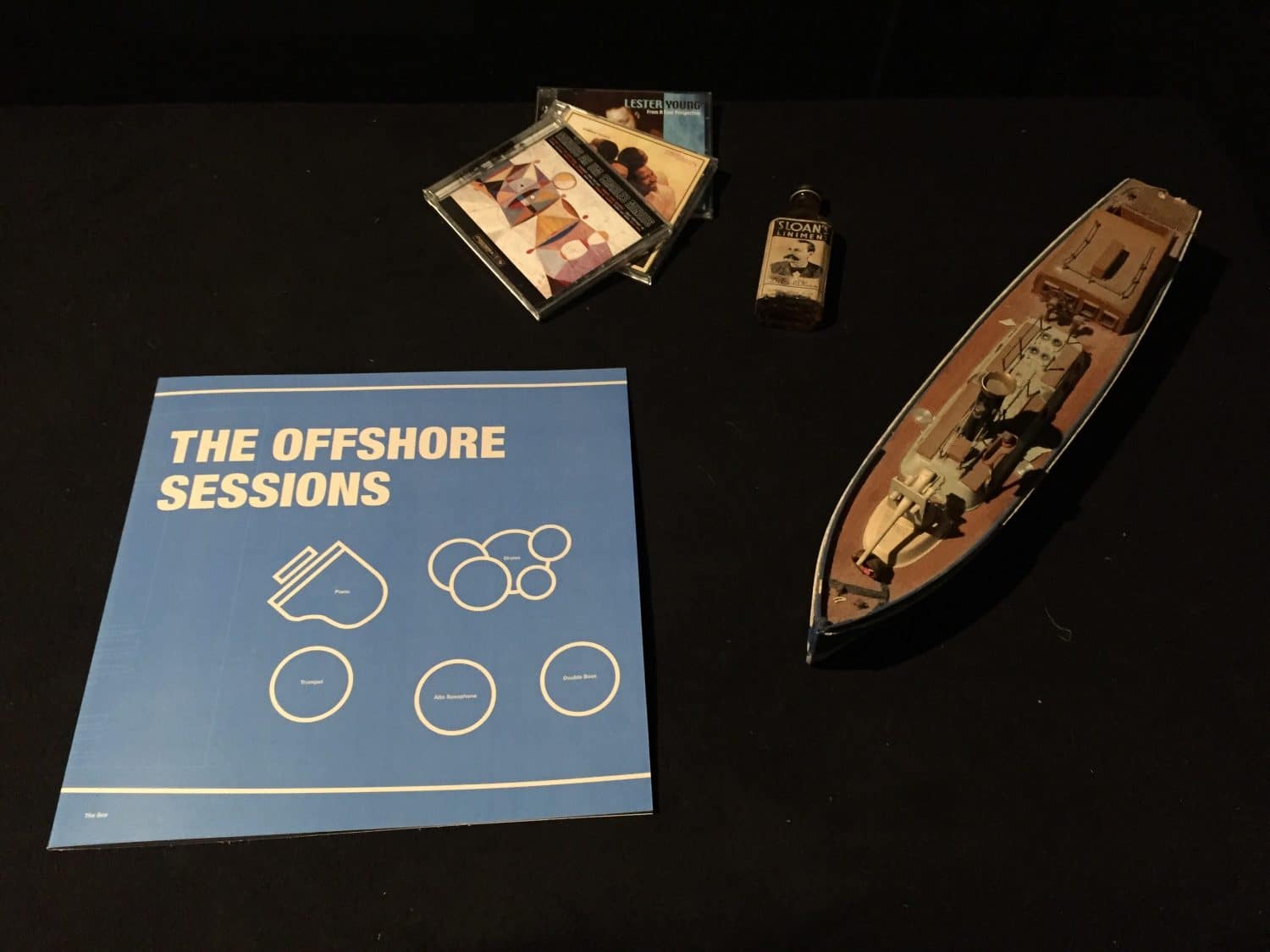

“I was walking around the room, picking things up, putting them down. I found this amazing collection of classical and jazz music, and I worked out how to use the stereo.” Novelist Wyl Menmuir is telling me how his short story/ fictional LP, The Offshore Sessions, began. “I started putting on proper old-school jazz and reading the liner notes, then the photography books. I started thinking, what if these people in these photograph books were jazz musicians, what if they got together to create this improv album? I came across a model boat and thought, what if it happened on a boat? What if they had an improv night on a boat in the Carrick Roads? What if…? What if…? From the objects I found, characters emerged. It was so different to how I normally worked, stories would suggest themselves. I just – played, for days.”

The connexion man

Somewhere in Redruth, up two flights of stairs and a ladder, I’m shown an attic of images and ideas. It’s the same room that kicked-off a hundred what-if’s in Wyl, and it’s like sneaking sideways into a mind that isn’t mine. The mind belongs to Bill Mitchell, WildWorks founder, artist, and landscape theatre-maker.

The Beautiful Journey, 2008 (Wildworks/Steve Tanner)

Bill died in 2016. Up until the weeks before his death, his attic was private. There are shelves of books and sketchbooks, CDs, records and DVDs. There are scenes created in tiny sandboxes, and collections of sheep, bottles and snowglobes. There’s a tin box marked ‘Dad’s business’ and another marked ‘hate’. There are birdcages and aeroplanes hanging from the ceiling. There are dolls and a pile of scissors. There’s dried-frog roadkill and water in bottles from rivers round the world. Sue Hill, Bill’s partner, shows me around then leaves me to explore. There are mirrors too, tucked into small corners. I’m caught off guard by my own face – wide-eyed, snooping, part of the scenery.

"It was so different to how I normally worked, stories would suggest themselves. I just – played, for days"

Brimming with things and rich with suggestion, whatever’s on your mind would find a hook to hang on here. That day, fresh from finishing it, Riddley Walker is on mine. I see Russell Hoban’s post-apocalyptic Kent everywhere – stags, stones, and Punch and Judy. Riddley, the novel’s protagonist, is a ‘connexion man’, a shaman-type figure, and his role is to spin meaning from events, signs and stories.

Later, hunting connections of my own, I search online to find Bill talking. “I do think of a lot of the work I do as collage,” he says. “I have quite a lot of cards dealt and my job is to find the connection with them, pop them in the right order and see how things work.” Cornwall’s myth-spinner; known for re-imagining the story-worlds of Orpheus and Eurydice, Odysseus, Tristan and Yseult and the Bible; there was clearly a connexion man in Bill.

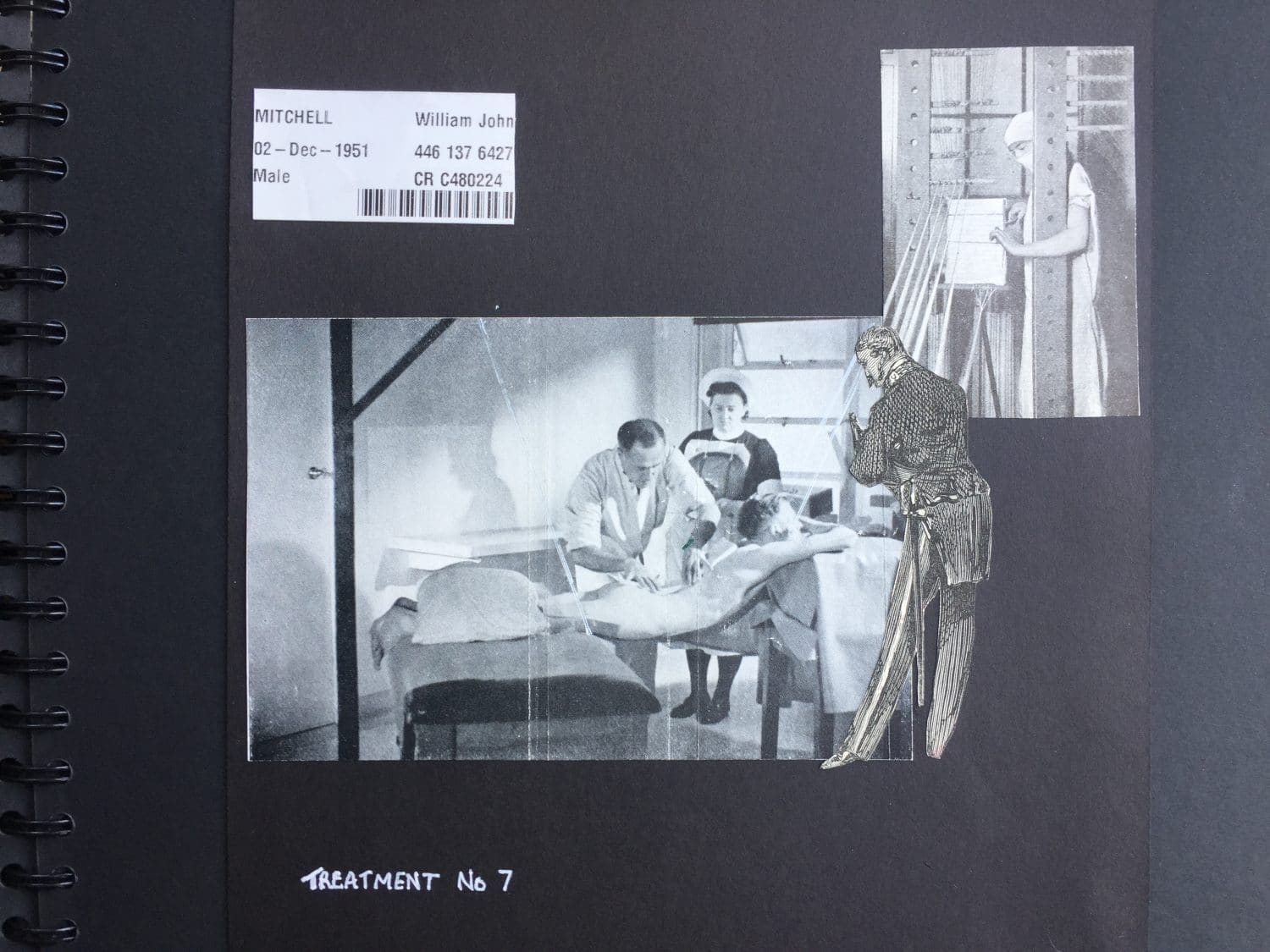

Bill’s sketchbooks

A connexion man, and a collection man. “He was absolutely a hoarder, borderline Channel Four documentary content, the proudest magpie,” says Seamas Carey, musician and Bill’s friend. “But it was all for a reason. It was all going in. That’s what I learnt from him. He had this huge input keeping his output going. He was a true artist, more than anyone I’ve ever met.”

The attic opens

When Bill died, the attic stayed, fit to burst. “I don’t think he, or I, understood just how much of a gatekeeper I would become,” Sue tells me. The hidden room had always been Bill’s backstage. “It was a personal thing, which became his public output,” she says. “And somewhere in the middle, I had to decide where the one thing became the other.”

A page from Bill’s sketchbook, ‘The Miracle Treatments‘

What starts when an artist stops? Working with museums to preserve Bill’s work, Sue describes the strangeness of putting Bill’s visions ‘on file’ – numbering and cataloguing empty pages in a barely-touched sketchbook, the topsy-turvy way an archive assigns value, how abruptly static it can all feel. Determined not to create a shrine and resisting the urge to hold on too tightly she resolved to bring people in, sharing the responsibility.

"’Come up and fix some things down for me, people might quite like to see them’ – it was his acknowledgment that he’d created something beautiful.”

“I had to make the process as porous as I could,” she says. “And it heartens me that in a sense Bill gave his consent. In the last week of his life, he said to our friend Mydd, ‘Come up and fix some things down for me, people might quite like to see them.’ It was his acknowledgement that he’d created something beautiful.” Sue invited artists in, gifting them Bill’s assembled worlds to look at and play with. “I never went up there when he was alive, and I found it very emotional” Seamas says. “But then, straight away, I knew I’d like to make something there.” Bit by bit, the attic hatch opened wider.

A box of stories

We are Splendid at Penlee House Gallery

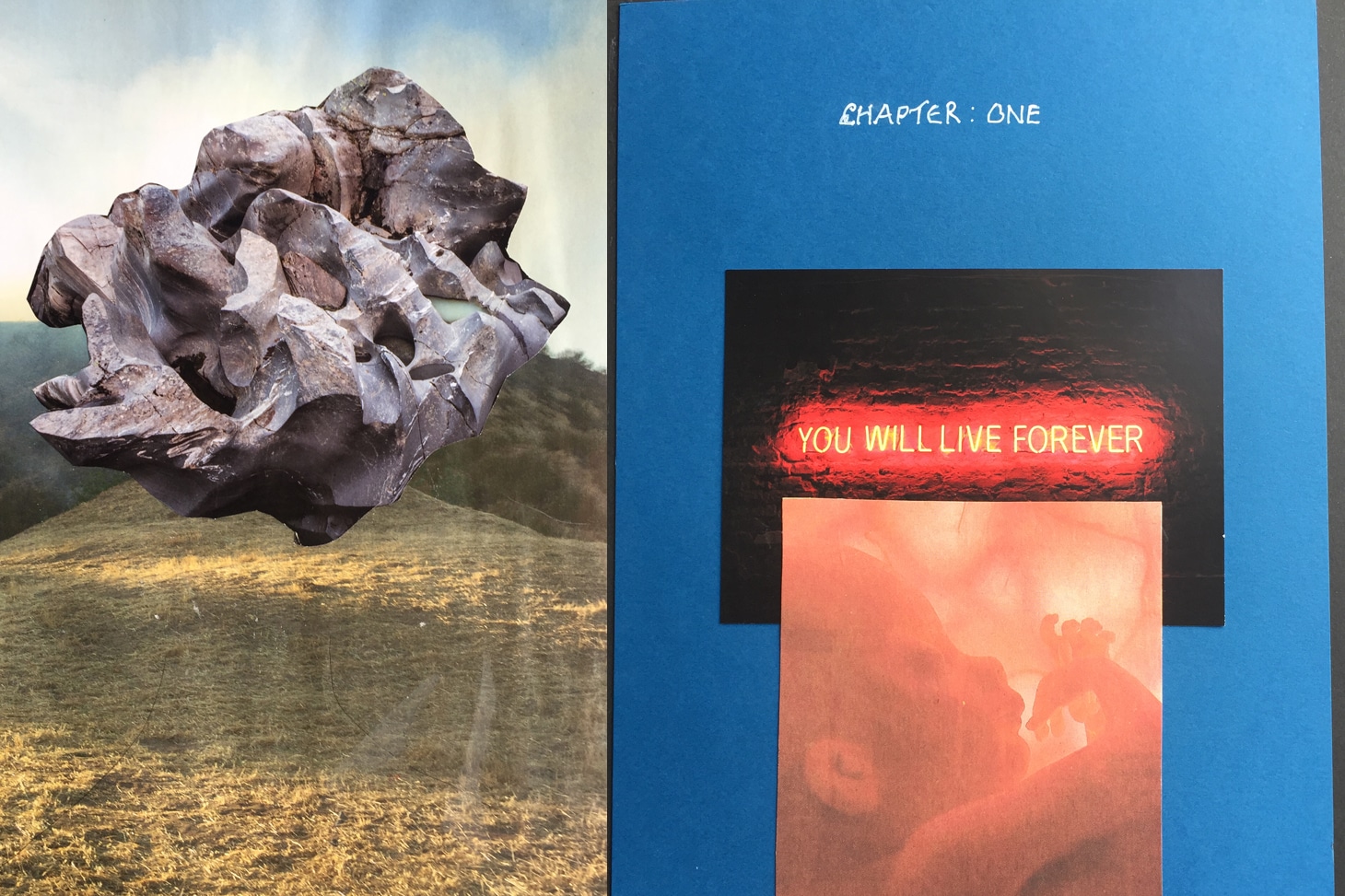

“It’s the scissors for me. Some of them are enormous, some of them are medical, some are domestic and some of them are industrial. And I’m just thinking, OK – there’s a box of stories waiting to be discovered.” Since Sue extended the offer, Mel Young has visited five times. A painter and performer, her piece We Are Splendid, made with Caroline Schanche, explores loss and memory through the tale of ‘the Splendid sisters’ and their creation of a secular bible.

Bringing their story to the attic, the Splendid sisters found a spiritual home, “I just want to keep going back,” Mel tells me, “it feels very beautiful and very deep. You’ll be wading through stuff, then suddenly – these real cracks of light.” Mel describes hours spent with Caroline, picking through objects, exploring the space, getting braver, moving things around, “Sue is so generous, she told us pick things up and change things, she didn’t mind what furniture we moved, where we were clambering around. We hung drawings up at the window, took lighting in there, all sorts.”

‘We are Splendid – Beginnings’, film still

We are Splendid is about the things we let go, in the aftermath of grief. In the attic’s amassed objects Mel and Caroline found an image of the things we hold onto. It became the backdrop for their short film, We are Splendid – Beginnings, “we made it the start of the journey for our splendid sisters, before they set up their secular church.”

The fictional sisters’ journey mirrors the attic’s own. “I’ve noticed a difference from when I first went, to now,” says Mel. “The space is clearer. It’s being organised, as it’s documented, there’s breathing space.”

“An inspiration – not a museum. There’s a fine line between those things.”

This year, the attic moves. Giving Sue’s front door a rest, Bill’s collections and work are being relocated to a lofty top floor space in Krowji studios. “It will change, it has to,” says Mel. “It’s really clear that what Sue wants, and what Bill would have wanted, is for it to become an inspiration – and not a museum. There’s a fine line between those things.”

Cracks of light

Sue Hill and Seamas Carey, ‘The House of Bill’ (Wildworks/Thom Axon)

“The original idea came from the armchair. I was sitting in this chair and going, OK, this is the centre of it.” WildWorks have always been site-specific, their shows embedded in the places they’re told and landscape cast as a character – whether a quarry, Devonport docks, or the streets of Port Talbot. Before the attic moved, Seamas wanted to make something that grew from the room itself – a site-very-specific show.

“There’s an amazing thing upstairs, and it’s not going to be there forever,” he says. “It’s great it’s going on a journey, but I thought, what can we do in this room? what kind of ritual could we do here, before it moves?” With lighting designer Lucy Gaskell and sound designer Alaistair Goolden, he created a show that led tiny audiences of 2 or 3 around the attic. “I wanted to make it about Bill, for Bill, but his work is so suggestive, I wasn’t going to make a biopic. It had to be more abstract than that.”

The Attic, ‘The House of Bill’ (Wildworks/Thom Axon)

“One day Sue left me up there. She said, I’ll turn the lights on for you, and as she flicked them on, one of those precise little halogens went *bing*, and picked out a little person. I started moving lights around. Making stories appear.” Inspired by the way ‘Son et Lumiere’ shows use light to create a narrative in the spaces of a building, Seamas, Lucy and Alaistair illuminated connections and suggestions – paying homage to Bill’s way of working. “There are these bird cages hanging from the ceiling, with angels and aeroplanes trapped inside,” he says, “at one point we made it so you’d hear wings flapping in cages and birds squawking. Then, it would feel like you were flying, you’d hear churchbells from far away, as if you were hovering above a town, then a tannoy, as if you were being welcomed aboard a plane.”

"I thought, what can we do in this room? What kind of ritual could we do here, before it moves?”

At the entrance to the attic, the audience was given a small tray of objects. Tiny story slices taken from Bill’s great collage, and asked to place them somewhere, at some point, during the performance. Alongside the sound and lighting, it brought the attic to life again. New scenes emerged, new suggestions were made.

Similarly, when the attic’s contents move, all of the amassed things and clippings and collections will be free for artists to use, on the condition they donate something back, whether a new piece of work or a Bill-style Ebay haul. The attic will grow and change, according to the Bill Mitchell playbook, resisting mummification.

The House of Bill (Wildworks/Thom Axon)

“If Bill were alive he would be adding to it constantly,” says Mel. “Six months from now it would look so different, he would have collected things, done loads more sketchbooks. For it to stop – it would be like a second death.” In its new home, the attic will be vastly more accessible, a site of ongoing collaborative activity, a melting pot of prompts and materials. “For this to keep being a generator”, Mel caveats, “I suppose it depends on how generous artists are about leaving things behind, about letting things become a part of something new.”

“You go to the house of someone who’s been making serious art and you think – oh, you were playing!”

Improvised group jazz

‘The Offshore Sessions’, Wyl Menmuir

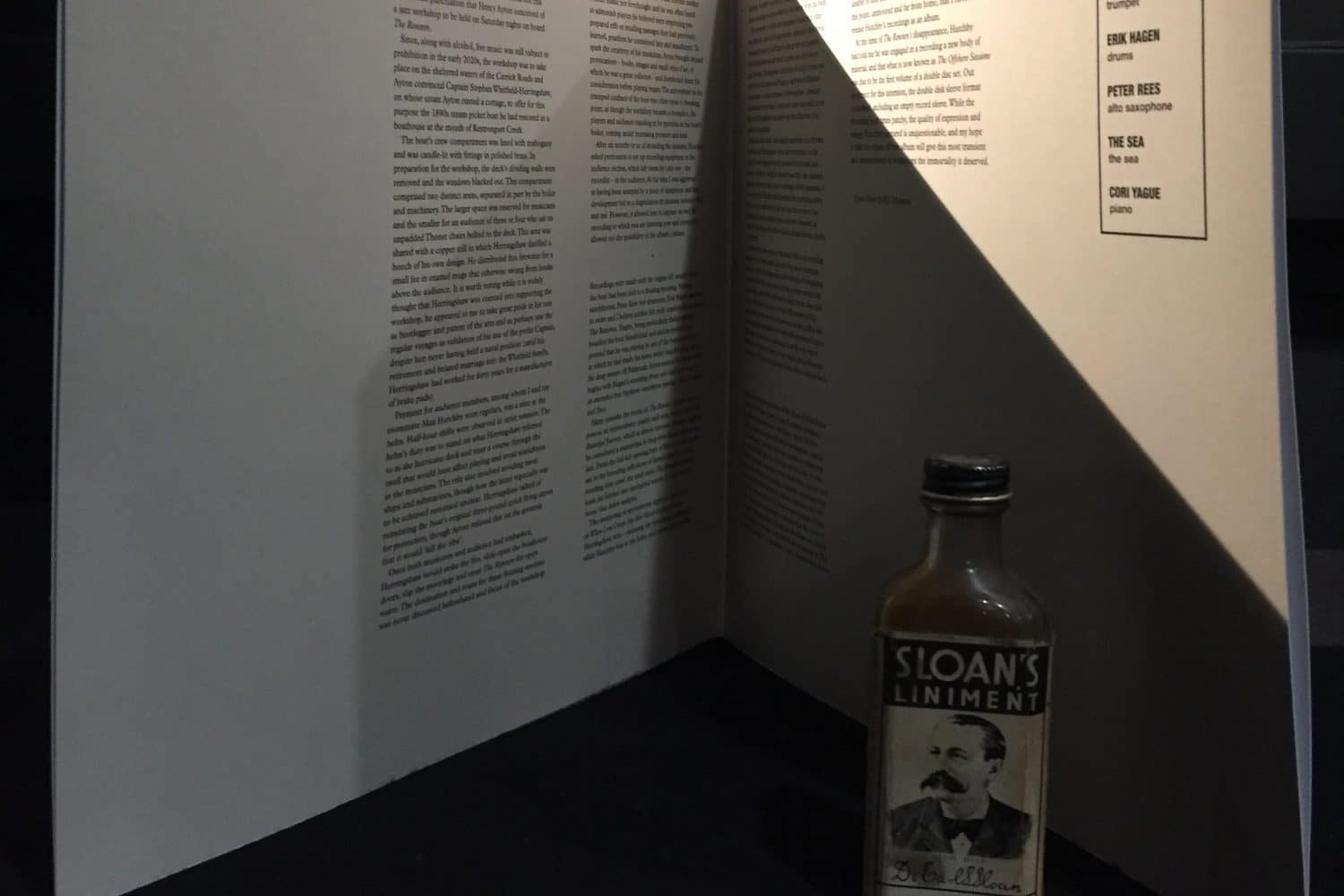

“There’s a little childrens’ book in there calls ‘How to Swim and Dive’. ‘Sloan’s linament’, that was one in a really good collection of little bottles he had.” Wyl didn’t know Bill well. He came to the attic as a writer, trying something new. “I’m always telling writers, you’ve got to take a playful approach – but it’s difficult. I’m sitting there thinking, I’ve got to be a serious writer, I’ve got to make serious art. And then you go to the house of someone who’s been making serious art and you think – oh, you were playing! I liked that.”

So Wyl played. Finding a model steamer, making it the setting for what would become a short story in the form of fictional liner notes, he describes what followed as a kind of design thinking. The position of the piano, constrained by the position of the smoke-stack in the real world ship; the length of his story, determined by sleeve note conventions. “George Saunders said writing’s a bit like optometry, you’re saying ‘better this way? Or this this way?”, says Wyl, “and this was a way of externalising all the stuff flying around my head. I think that’s what Bill was doing in his sandboxes, refining and refining and refining. I tried keeping the feel of improvisation in what I was doing.”

An attic detail (Steve Tanner)

“When Sue saw what I’d made, she said, ‘So you know Bill was a drummer? That he’d get together for improv sessions a bit like these?” Without knowing anything, through coincidence or osmosis, Wyl had brought Bill into the story, “I was aware I was in his space. I was sitting at his desk,” he says, “using my own pens but surrounded by his pencils, and his little knife for sharpening them. I suppose there was an element of conversation in it.”

More typically found at a (remarkably) pristine desk, in Bill’s attic-full of memories, Wyl was struck by how stories could be wound tight within things. “I knew it had to become a physical thing”, he says of his story “not just something I wrote down.” Working with graphic designer Dion Star, he made his LP sleeve, complete with the most minute details, missing only the music. “The track-listing’s on the back,” he says, “I thought, at some point in the future I can give that to a group of musicians, and say – you’ve got all the names of the song, and the rules of how you perform together – make the album.”

The attic, in 360° (Scott Fletcher)

Leaving a question mark, a gap in his own work, Wyl’s LP throws down a creative challenge in keeping with everything the attic has become, and the role it’ll play over the next few years. “They aren’t completed stories up there, there’s a feel of unfinished work. Bill kept everything in flux, and I think it’s got to go back to being in flux to be a really great space again. And then, who knows what’s going to come out of it?”

Another life

An artist and theatre-maker herself – Sue’s work, life and love were knit tightly together. “The grieving process is not within your control,” she tells me. “It happens to you, and you have no mastery over it. But, it is an exercise in finding again, making new, the person who you are. Bill and I worked together and lived together, so we were more intensely bound than most married people I know. When we met, and fell in love, we always said, ‘We’ll be together as long as we want to be together, and when we stop loving each other, it stops.’ That’s how it should be. But, 40 years later, you turn around and you go – ‘My God, I cannot imagine my life without this jigsaw piece part of me.’ We were each others’ best friend in so many ways. There is a whole process of unpicking that. And as part of that process – the idea of still being responsible for Bill’s attic in ten years’ time? That needs to not happen.”

Bill Mitchell (Steve Tanner)

The attic is being digitally captured in situ, a 3D ‘hummingbird’s view’ of the space, kept for the future and interwoven with the artworks it has inspired – artists Scott Fletcher, Steve Flanagan and Ciaran Clarke have collected a mountain of digital data, more than it would take to construct a whole gaming landscape – and photographer Steve Tanner is capturing the insides of every box. But then, after its life at Krowji, Sue talks of one day separating, parcelling up and scattering parts of the attic across the world, sending pieces of Bill’s collections to friends and collaborators everywhere, letting it go for good.“When we had the idea that eventually these precious things would go onto have another life,” she remembers. “He was very excited about that.”

Setting his recording in 2026, Wyl has about six years to find his jazz musicians, and finish the record.

And so Bill’s collaborators multiply, and so the stories go on.

+