(We also heard whispers of stealing across rooftops with giant wooden frames of pink string in the dead of night – but that’s another story.)

Stranger Collective: How did you get into this line of work?

Dan Arnold: I have always made work; throughout school, art was always what I wanted to do. I grew up in the middle of nowhere in South Wales, Mum would cut the plug off the television. We’d go outside. I spent a lot of my time in the fields and the woods building things and looking for things. The natural world, and the processes involved in it, have undoubtedly had the most powerful influence on my practice.

After a foundation course in Bristol I did an Illustration BA in Brighton. Several years later, after spending a lot of time overseas exploring and researching and working in all sorts of jobs to pay for it, I did an MA in Illustration (Authorial Practice) at Falmouth. I graduated a couple of years ago and I’ve set up my studio in Penryn in an old sail loft.

SC: What led you from illustration/ 2D work to working with objects and installations? What do you like about working with tangible objects and 3D spaces?

DA: Both are fundamental to my practice and the process of building something holds the same integrity for me, whether that building takes place on a piece of paper or in a room. Only the material changes; the process is often the same – a smaller component repeated to create a bigger form.

I went from small drawings to giant murals and then onto drawing on objects like dugout canoes and trailers, but a 3D element has always been there. Back in Brighton, drawing wasn’t communicating what I wanted it to for my final project – it needed to move, so I drew an object out of physical materials and made it hover. Thinking about it, I guess that’s part of it, a drawing remains on a 2D plane…drawing in 3D with other materials allows you to build an environment, to create a space that interacts with someone.

Even a mural allows you to walk alongside in a way you can’t do with a smaller piece of paper. Larger work allows a different kind of immersion – more of an attempt to create the feeling of being immersed in nature or an environment; a forest, a field or a coral reef.

“I remember as a kid making huge figures out of hundreds of pebbles and went turbo if you gave me a box of LEGO.”

SC: From an iceberg made of thousands of monkey knots to giant floating chairs made out of cocktail umbrellas, why do you think you’re so attracted to using lots of small things to create impact with a bigger whole?

DC: Haha. Yep, I always have been…my drawings are the same. I remember as a kid making huge figures out of hundreds of pebbles and went turbo if you gave me a box of LEGO. As my practice has developed, the reasons why have become clearer; basically I think it all goes back to nature and the processes involved. Everything is made up of something smaller, down to a cellular level and beyond, everything is made of components some visible, some invisible.

My piece, #Chemical Archipelago (The Party’s Over), made out of over four thousand cocktail umbrellas, colonising a dining set, for example, draws direct influence from a coral reef and the Spirobranchus worms that inhabit them. As a result of repeating a process something larger appears; something grows and evolves. Often that is what I’m striving for, to set something in motion and then let it grow organically. One cocktail umbrella planted in a table begins the process and the size of them informs where the next one goes. I purely become the planter or builder; the umbrellas are what’s making the work, they are the chemical organism.

Another example would be A Murmuration of Light, a digital sculpture built initially for planetariums that revolves around creating a digital murmuration out of pixels. We worked with programs that allowed us to create entire environments and weather systems that the flock of pixels moved through. How they reacted was dependent of various parameters that we set in motion, but ultimately the end result was out of our hands in many ways, again reflecting processes in the natural world. Murmurations, coral reefs…both examples of amazing things made up of countless individual components.

Looking out from the studio now, the estuary beach is made of thousands of pebbles, the trees covered in countless leaves, the water home to bazillions of tiny organisms. Shit, I don’t understand it at all and maybe that is why I build these things, to try and understand it.

SC: Ties in nicely to Stranger Collective’s obsession with collective nouns… Can you tell us how you approached our window project/ the thinking behind it?

DA: The League of Strangers is a great idea, a web or network of freelancers and remote workers. I think the idea of interconnectedness rolled from there. The Stranger Collective space on Killigrew Street is the nucleus, or initial hub of this League; it’s where the collective begins, the big bang. I wanted to explore webs and things created out of smaller components (no surprise there). Everybody involved will be interwoven with each other and events organised by the Collective.

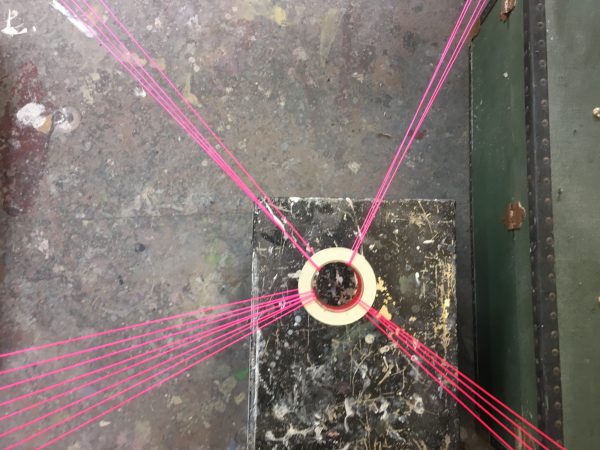

As a result, the installation primarily takes inspiration from spider webs, images of the big bang and sun bursts. The materials used also reflect the design and planning elements of any practice; the pink string is builders’ line used to mark out plots and plans onsite. The string threads around fat rolls of masking tape – again, a key material in nearly every creative discipline. These rolls also form the centre points, or nuclei, of the pieces, acting as portals into the studio space and echoing the viewing ports you find on hoardings around building sites. The brief was focused yet very much open to interpretation, which I liked.

“Looking out from the studio now, the estuary beach is made of thousands of pebbles, the trees covered in countless leaves, the water home to bazillions of tiny organisms. Shit, I don’t understand it at all and maybe that is why I build these things, to try and understand it.”

SC: From a bold and very relevant concept to the reality of making it happen, what were the biggest challenges on this project? Did you get knotted up in pink string?

DA: Ha, I got super tangled up in string. The proof-of-concept model I built was a lot smaller and the larger sizes were bigger than I initially thought – scales exponentially growing, so materials had to be scaled up accordingly. The technique I developed for the weaving meant threading string through a series of holes and around the masking tape roll – very long pieces of string, that was a challenge for sure.

It was physical work too. I probably looked like a hectic spider doing contemporary dance. Taking the string off its roll inevitably led to massive tangles that took ages to untangle. Occasionally magical knots would appear in the middle of the string somehow, which meant unthreading whole parts again. It was nuts really and therefore pretty challenging. After a lot of swearing, with these projects you tend to realise that being as calm as possible is the best approach.

“It’s rewarding to make a piece of work that will be seen outside a gallery context too; something that becomes part of the community we are all in.”

SC: Unsurprisingly, working with large amounts/ numbers of small objects is super-fiddly then… do you get a kick out of discovering methodical ways of making it work – finding order in chaos – or do you just curse yourself with coming up with these ideas?

DA: I think I find it meditative at some level, and ultimately rewarding when something larger starts to appear out of the smaller components – especially when the idea goes from a theoretical idea into a reality. Ask me when I’m in the middle of a project and I’ll probably be cursing myself for sure, but I’m not sure I can help it. If you’re going to do anything then you might as well push yourself as much as possible.

SC: What did you find most rewarding/ satisfying about this project?

DA: I liked the challenge of building something that responds to a brief and works within practical restraints like light etc. It’s rewarding to make a piece of work that will be seen outside a gallery context too; something that becomes part of the community we are all in. It’s great to have now installed the project in such a public spot – I’ve already had a couple of messages from people who’ve wandered by the piece.

SC: Are you tempted to take up weaving or macramé – or are you never touching string again?

DA: Macramé reminds me of school and therefore brings me out in cold sweats. One day I’ll face that demon if I end up with too many hanging plants in the studio, but until that moment I’m happy to leave it alone. Other weaving projects, shit yeah…I’m well up for them and would love to collaborate with weavers and knitters. Drawing in thread, giant tapestries…that’s rad.

SC:What next? Any exciting projects on the horizon you can tell us about?

DA: A couple of things floating about. I’m helping curate and hang the MA show next month which is cool and an honour to have been asked. I’m also working on a collaborative sculpture with a blacksmith in Bristol, based on creatures I’ve designed so we’ll be drawing in metal soon enough, always good fun. There’s a possible bigger residency but that’s staying under wraps for now until more elements are in place.