Welcome to the second issue of our online magazine, Strike. Watch me use the word ‘issue’, as if it had landed on your doorstep in a nice brown paper envelope. But you can read our pages in any order you like, of course. Skip back to October’s musings if you fancy, tunnel through the links – these little peepholes we’ve drilled in the pages. Notice how I used the word ‘pages’ too. Print this one-off if you like, onto paper. See if it changes things.

Say you skip back to here, you’ll find Stuart Nolan explaining how ‘user illusions’ work in digital technology. “It’s not a desktop,” he reminds us. “And those aren’t folders, and those aren’t files, and that certainly isn’t a waste paper bin. These are all convenient illusions.”

Reading and writing in the digital sphere are run through with concepts borrowed from earlier or obsolete writing technologies. We’re not letting go of paper lightly. I’m drafting this on Word, manipulating an A4 proportioned and 3D-shaded paper-ish graphic. But behind the mask of familiar terms, the processes and behaviour that we commit our thoughts to – what? (not paper anymore) – have changed drastically.

“Our writing tools are working on our thoughts.” Friedrich Nietzche

Process this

I’ve always found ‘word-processing’ a sadly perfunctory phrase – images of words as mass-produced sausages, sentences a factory amalgam of parts. Bits and bytes on a string. But I do engineer my writing on screen. I swap some words for others, shift parts to tesselate, shave sections to fit. It can feel more like LEGO than literature. “Word processors have systematised the logic of assembly,” notes Argentinian writer Alejandro Zambra. “Today more than ever the writer is someone who builds meaning by putting pieces together.”

“That’s not writing; that’s just typing,” Truman Capote said witheringly of Jack Kerouac in the 1950s. In 1881, through illness, the philosopher Nietzsche moved to a typewriter. He didn’t take to it. “Our writing tools are working on our thoughts”, he bemoaned. “The machine is impersonal, it deprives the piece of work of its little bit of humanity.” Things have moved on since then, but the hunch (or the fear) that different technologies tweak the content we’re capable of still pervades the writer’s psychology.

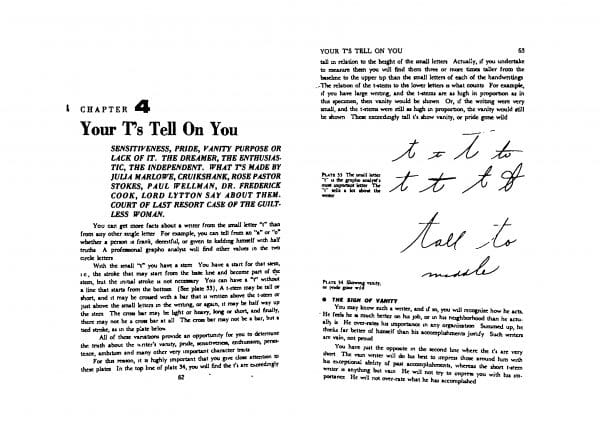

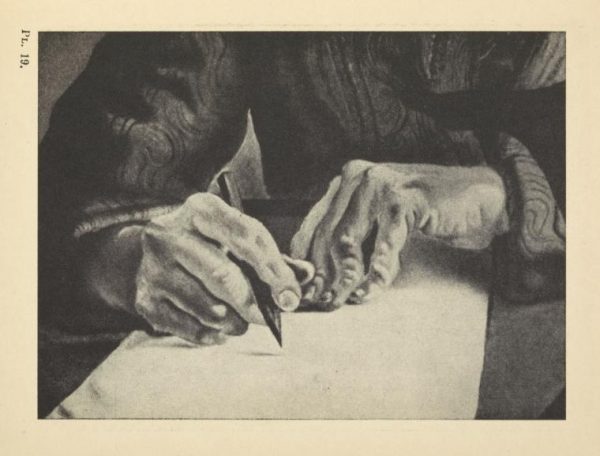

It’s understandable. Handwriting is necessarily linked to the body, and the body’s entwined with the self. The writing self traces each letter form physically, whilst the tapping self works in code, with repetitive movements that bear no formal relation to the words. Consider the age-old practice of handwriting analysis. A graphologist might claim to derive your deepest secrets from the way you curl your ‘y’s. Like it or not, the theory goes, your self sneaks onto the page. And when I draft by hand, for better or worse, I feel a different part of my brain at play. Free-er, more fluid, perhaps. But does that mean that the writing itself comes out differently?

Joined-up thinking

Neil Gaiman seems to think so, writing the majority of his novels by hand. “I started with Stardust,” he says. “It was (in my head) being written in the 1920s, so I wrote it by hand to find out how writing by hand changed my head. And it did, it really did…So I kept doing it.”

And Gaiman found more than just the period immersion he was looking for. He found his own way of writing better, or at least differently. Handwriting fires different neurons, and requires focus-pulling motor skills. Speaking to The Guardian, psychologist Eduoard Gentaz explains that handwriting is a distinct and complex cognitive process: “Feeling the pen and paper, moving the writing implement, and directing movement by thought, children take several years to master this precise motor exercise.”

“I was sparser, I would think my way through a sentence further, I would write less, in a good way,” explains Gaiman. “And when I typed it up, it became a very real second draft – things would vanish or change.” Note “typed it up”. Because let’s not forget – laptops are great. They’ve provided wider general accessibility to educational tools and opened up writing. They’re indispensable to most of us.

A quick survey of the studio confirms we all do a bit by hand and a bit on screen. Next year, we’ll be putting on a bookbinding workshop with bookbinder and playwright Emily Juniper – and if anyone understands the pull of paper it’s her. “I write thoughts, snippets and words, magpie-collected on envelopes, receipts, anything to hand,” she explains, describing her writing and making process. “Those initial thoughts are instant and handwritten.” But then, like most people I spoke to, she moves to the screen and dictation: “I’m a big fan of a software that lets you audio type. I’m dyslexic and hate having to stop to find the right spelling”. There’s a working balance between inspiration, intuition and convenience. In some ways, we’ve got it all – to each method its moment.

"People enjoy the sight of their own handwriting as much as they enjoy the smell of their own farts." W.H. Auden

False loves

Perhaps then we should be wary of wary of fetishizing handwriting. W. H. Auden once quipped that “people enjoy the sight of their own handwriting as much as they enjoy the smell of their own farts”. In the opening scene of Her (Spike Jonze, 2013), protagonist Theodore Twombly works producing identikit ‘handwritten’ letters for paying customers. The demand for this service, in the near-future tech-heavy world of Her, stems from the idea that handwriting carries humanity, but any actual bodily link to the writer is fabricated, steeped in empty nostalgia.

Auden went on to say, “Much as I loathe the typewriter, I must admit that it is a help in self-criticism. Typescript is so hideous and impersonal to look at that if I type out a poem I immediately see defects which I missed when I look through the manuscript.” Perhaps bad writing can hide behind an elegant hand (and vice versa).

Zambra suggests that word-processing frees his writing from preciousness: “I think there is a central fact: because of computers, text is ever less definitive.” Because there’s a crucial difference between the typewriter and its digital successor. Writing on screen is flexible; changes can be made without trace, a backspace works like magic and nothing is sacred. “A phrase is today more than ever a thing that can be erased,” he points out. “And the proliferation of words is such that we must like ours a lot to keep them.”

“A phrase is today more than ever a thing that can be erased.” Alejandro Zambra

Unseen collaborators

“A phrase is today more than ever a thing that can be erased.” In our always-connected environment, where each tap is encoded as data, there’s a sense in which this is more and more literally true. Google Docs and co have created a system where writing exists in a universal space. Words float free of their origins. We’re surrounded on all sides by ‘authorless’ text, speaking to us from the corners of digital spaces.

What’s more, our devices have started chipping in with their own ideas. Gmail’s ‘smart reply’ uses machine learning to suggest email responses based on our previous emails. It’s an odd collaboration in communication – our own words typed back at us, by a (slightly off-brand) robotic twin. Smart compose goes a step further and finishes your sentences as you type. When Nietzche worried that our writing tools were working on our thoughts, I doubt he’d foreseen just how hard they’d end up working, and quite how close to our thoughts they’d come.

Writing is personal. Perhaps that’s why we still protectively wield graphite and ink. There’s a physicality, a there-ness, to ideas; a trace of ourselves on the paper. When I asked her why we still need paper, pens and notebooks; Juniper put it this way: “In a digital world, words are so disposable. But books give them a stage. They allow us to hold stories, to re-examine, to re-engage. It’s a ritual, opening a book. It’s like you’re climbing inside and not just vaguely scrolling through.”

It’s hard to name all the ways our writing tools change our writing; but as they work on thoughts, I’d say it’s probably worth keeping our thoughts on them.

+