It’s in the corner of your eye, just out of reach; a twitch, a thought, a glimmer. We inhabit a world built of illusions, both wondrous and worrying.

It’s always been this way. We can only move through life by missing the full story. It’s a truism that’s been exploited by magicians for centuries, finding hidden pockets of communication to mislead us, read us, amaze us.

Our interactions with digital technology are governed by startlingly similar principles. And, as the Internet of Things embeds digital technology into our physical environment – through sensors and voice assistants, responding to our words and gestures – what are we learning about human interaction?

And where are we heading: into magic, or madness?

We thought we’d turn to the experts…

Damon Civin

“I work as a Principal Data Scientist at Arm, I run a team of data scientists at Arm, based at our office in San Jose. I take data from various things – sensors in the physical world, or data that’s collected online in the digital world – and then try to solve problems with it, to turn it into something valuable and useful.

We’re currently working towards the Internet of Things (IoT), building lots of sensors to gather information and control things in the physical world. We’re looking at bringing the digital world closer to the physical world through IoT.”

Stuart Nolan

“I call myself an Applied Magician. I take the techniques from the world of magic and apply them to other areas. I do a lot of work for Innovate UK, who fund technology innovation in the UK, so I get to see a lot of very cutting edge ideas.

I work on long-term research projects where people are trying to deal with questions of: How is this magical? How is this creating an illusion? How is this deceptive? This is often to do with issues of attention control. So I take skills we already have from performance and apply them to technology developments.”

Phyllida Bluemel: So, what’s Machine Learning, and what’s it being used for?

Damon Civin: Over the last few years compute power, amounts of data and techniques gathered from the research community have combined to make it easier – for some tasks – to gather data and push it through statistical models than it is to write explicit code.

Some people are trying to recreate human intelligence. Others, like myself, are not – we’re using it as an engineering tool. Human intelligence is a helpful inspiration. But if we can do something else, we will. The folk wisdom on this is: when you build an aeroplane, you take the principles of flying, but you don’t put feathers on it. At the moment machine learning is being used a lot for visual and speech recognition. Assistants like Google Home and Alexa run machine learning models to recognise your voice. Speech synthesis is also something we can do now.

Stuart Nolan: A lot of the projects I’m looking at use machine learning in these ways. It’s solving some thorny problems, for sure. But, for good reasons, we’re still only focused on specific channels. Speech, sight and gesture are all channels of communication and we might apply machine learning to those channels separately, and make some progress there, but humans interact in a messy way, using lots of channels at the same time. We miss how important those channels are when we use media to communicate.

"When you build an aeroplane, you take the principles of flying, but you don’t put feathers on it"

Armando Lucero, the sleight of hand magician, taught me about ‘fidgets’ – moments when you’re communicating with somebody and they fidget, or pause, have a little cough, an ‘um’. Unless I draw your attention to those things, you filter them out as if they’re not there. So, for a magician, it’s perfect place to hide things, inside a fidget.

I was part of a project called Being There: Humans and Robots in Public Spaces, working with the Nao Robots (designed to interact like five year olds). We asked, “How will we be interacting with robots in public spaces in the coming years?” The puppeteer Dave McGoran was involved, and he pointed out – lesson one in puppetry – that none of the engineers had made their robots breathe, because robots don’t have to breathe. But, as soon as you make something breathe, it becomes lifelike. All these things are channels of communication. When you talk to somebody, you control your breath to ensure you’re not talking when they are. The way we breathe becomes synced to the person we’re talking to. If we start applying machine learning to how breath is a communication between people, we’ll open up whole new areas of useful machine learning.

DC: This idea of physical objects that behave more like biological ones is really interesting. There’s a need to adapt physical technology to humans and biological systems. That’s going to be a huge part of the IoT. There are people working right now on brain to computer interfaces; technology that allows you to communicate digitally through sub-vocal communication channels. When you think about something your bones vibrate – there’s a channel of communication there that’s sub-vocal.

Messy problems are a great fit for machine learning. There’s lots of data and multiple dimensions, more features and more input to work with. And it’s an academically diverse field – you’ll be at a conference talking to a neurobiologist one minute, a linguist the next. Mess is good.

"Artists have an instinct to break things. Flipping things to their opposites is an artistic strategy. The robotics engineers kind of hated us..."

SC: Spot on, messiness is great. And the sub-vocalising you were referring to – in part, that’s an ideomotor response, which has informed a lot of my own research. When we listen to somebody speaking, we actually make the same shapes they’re making with our own speech mechanisms. People who’ve had their throat and face muscles injured or immobilised, can struggle to understand speech.

This fascinates me, how mirroring is part of communication. The ways we map and bounce off each other are the messy parts. It’s going to be interesting to see how machine learning tackles that. Partly because it will expose an awful lot about the things we do without realising we do them.

At Queen Mary University they’re working on vision systems that try to work out the emotion a person is feeling. They tested this by putting the system on a Nao Robot, and having people interact with it. They wanted people to experience different emotions so the system could spot them, but people were invariably smiling and laughing, because they were talking to a cute robot.

Artists have an instinct to break things. Flipping things to their opposites is an artistic strategy. The robotics engineers kind of hated us – they spend all day trying to make things that work, and it felt like we were trying to break their stuff. But, we wanted to make these cute robots dislikeable in some way. What if one of them was to be racist or sexist or creepy… what would happen? We found that if the robots were saying nice things, the humans would think they were cute. The moment they stepped over a social line, they’d turn away and look at us; ‘Why did you make it do that?’ They understood that this is a puppet, even if it’s autonomous to some degree.

DC: Yes, allocation of responsibility will become increasingly important. Racist and sexist robots are a genuine issue we face right now. If you take data and that data contains historical biases, whatever is in the data is going to come out in the model when you train it. There’s no magic there.

SN: Right. If it’s garbage in, it’s garbage out. I’ve worked on a project before to create an AI that believes in magic – a superstitious AI. And superstition is essentially false correlations between data. We taught it a fortune telling system by Pythagoras and took data sets from online personality tests. We asked the AI to make a correlation between birthdates and personality types. And, this is the interesting thing – audiences I tried it with would invariably find truth. They would say: “That’s incredibly accurate. That’s just like me”.

DC: We have this tendency to tell ourselves stories. That’s at the cutting edge of AI right now – how do we train models to build their own model of the world that they understand?

But, to turn what you said around the other way: we find these correlations, whether they exist or not. And at the moment we’re in the middle of a really big experiment – or thousands of experiments. When you go on Facebook, you don’t see the same as everyone else. There are tens of thousands of different versions being tested, all at the same time. And the data being gathered is changing our culture. Maybe it takes a racist Twitter bot, or some kind of superstition to make us go: “even without AI, that kind of data-driven thinking is having an effect on our society”.

For example, when they predict recidivism (whether someone is going to offend after being released from prison) these models are based on historically racist data, because, especially in the US, there are more African–Americans in the prison system. I hope that we’re in a period of becoming aware of our implicit biases, because they’re being shown up when we try and automate something. The machine learning community has a role to play here.

"It’s not a desktop, those aren’t folders, or files, and that certainly isn’t a waste paper bin."

SN: You absolutely spotted the direction I was going. We ended up calling our superstitious AI Parei, short for ‘pareidolia’ – the tendency to find meaning in what is essentially random patterns. I hope that I share your hope. I think that I do. But, in my work I’m often commissioned to produce a performance about technology that raises issues and concerns. I get to play a couple of steps ahead of where we’re really at. And to play with potential futures rather than ones we’re necessarily going to have. I can play in fiction as well as in reality.

There’s a 1993 paper by Bruce Tognazzini about how designing software is like designing magic. He was an amateur magician and one of the first interface designers at Apple, responsible for the Desktop metaphor. They called it the ‘user illusion’ – it’s not a desktop, those aren’t folders, or files, and that certainly isn’t a waste paper bin. These are all convenient illusions, but we’ve stopped using that word. It’s a shame, because if we think of ourselves as illusion designers, it can focus us on potential problems. In the same way you hope a racist AI might make existing issues visible, I think keeping an eye on the fact we’re illusionists will help too. We’re moving into an age where it’s going to be difficult to tell what’s real and what’s not in audio, text, video and image. We need to realise that what we’re doing is creating incredibly powerful deceptions. Fake news is obviously a big part of that.

DC: Thinking of user interfaces as illusions is spot-on. Spotify’s founder, Daniel Ek, has said one of their early design goals was to create the feeling of all the world’s music on your desktop. Human reaction time is 200 milliseconds, so the idea was for it to take less time than that – between pressing the button to hearing music – to give the perception of instantaneous music. They did all sorts of tricks in the UI to distract you, digital fidgets, if you like; because they couldn’t quite get it down to 200 milliseconds.

Like you say, we are at this weird time where we’ve got technology that can generate essentially synthetic information. There’s no objective reality on the internet now, if there ever was. That’s coming into stark relief.

SN: Of course. In some ways there are amazing, beautiful, powerful possibilities with all this technology, and then there are terrors and fears associated. Although, as a magician, that gives me a rich playground. Magicians have always had a bit of an arms race with technology. Historically we like to find emerging technologies the public don’t know about and use them to create wonders. You might have a short window before the public understands the tech and it ceases to be wonderful.

"Magicians have always had a bit of an arms race with technology."

PB: And so, do you think there’s an end point to magic, where we become so technologically advanced that it all ceases to be wonderful? Will we stop believing in magic?

SN: I think belief is the wrong word for what magicians do. Magicians don’t ask people to believe what they’re doing is real. They might theatrically ask them. Tim Crouch, the playwright, talks about auto-suggestion. What you’re doing in the theatre is giving the audience a suggestion and if they take it on, it becomes an auto-suggestion, they experience it as though it’s real. But, at no point should you ask the audience to believe.

He quotes a line from Shakespeare like: “Think of a horse”, and says, “I hope Shakespeare wrote that line because he has a great understanding of theatre, not because he couldn’t afford a horse”. If you put a real horse on the stage, it limits people’s imagination, all they can think of is that horse. If you ask people to think of a horse, they can think of all manner of things to do with that horse. There’s a crucial different between saying “believe there is a horse on the stage” and “think of a horse”.

Magic is asking people to think, not believe, these things. And we can always think of things. New technologies and new scientific discoveries won’t cease to be wondrous and amazing, because we won’t run out of things. There’s a real difference between believing in magic, which is superstition, and thinking of the magical in a theatrical and imaginative sense.

DC: And that’s really the core of what innovation is. Often, you see innovation coming from people who are learning something, rather than experts, partly because they don’t know what’s impossible. Arthur C. Clarke had three laws. The third is kind of hackneyed, that, “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”. Which almost feels like what we’re talking about here. But, the second law is “the only way of discovering the limits of what’s possible is to go a little bit past what’s possible, and in the process you make it possible”.

SN: That second law is exactly what some magicians, me included, try to do. We go that step further, theatrically, and that helps our audience think about those things.

DC: Right, and app developers, Silicon Valley, that culture at large, it’s really about the same thing. It’s about creating experiences that give users that magical feeling. The first time I ever got an Uber – that felt like magic!

“the only way of discovering the limits of what’s possible is to go a little bit past what’s possible"

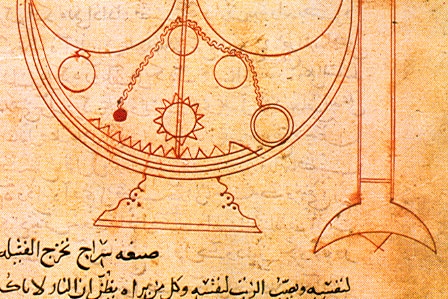

SN: I make a bold claim and then I edge away from it slightly. But I like to say that practically everything was invented by magicians. If you think of magic as a tradition going all the way back to shamanic practice, then there’s an obvious truth in that. But, you can strongly argue that magicians created the first programmable machine in 9th century Persia, or the first automata, or film – a great example of an illusion that we’ve forgotten is an illusion. All those things were invented as entertainments, although not simplistic ones. The Banū Mūsā, operating in 9th century Persia were entertainers, but with a rich cultural depth, related to power structures and religion at that time. They weren’t simply acts of curiosity – they were, much more complex than that.

DC: Innovation will often feel like a toy at first. We only start taking it seriously when there’s a lot at stake. You see a lot of tech ideas coming out of the gaming world, for example, that become extremely important in the real world. And hopefully as a culture, we won’t lose these generalist alchemist/mathematician/illusionist characters. A lot of serious academics, take Newton, for one, also came up with complete nonsense. You wonder, ‘was this speculation or did they really think that?’. You have to create some fiction to land on really important things. And, incidentally, that’s how machine learning works, right? It’s trial and error based. These models explore different possible outcomes and match the most likely one. That’s really all the algorithms do.

SN: One thing we do forget, when we do this ‘technology is magical’ discussion – I’m thinking of those conferences where a big tech company will say the theme is ‘technology is magic’ and all they’re really saying is ‘Wow. Technology. Cool’ – is that magic isn’t necessarily good. Magic is dangerous and dark, and that’s one of the reasons it’s exciting, it can be mysterious and troublesome. A magic show without a sense of darkness doesn’t interest me at all. It’d be like happy death metal. Good magic, and the magic I enjoy, has to be slightly creepy. That ‘…any sufficiently advanced technology…’ quote: I think there’s some truth and there’s some difficult things in it.

"We don’t take these things seriously unless there’s something on the line."

DC: That’s really interesting, the way I’d phrase it in terms of technology is this idea that if there’s nothing at stake, then there’s nothing of value. Think of Uber again – who are the creeps on both sides of that transaction? Or Airbnb. I stayed in an Airbnb in Iceland two days ago. It’s still an exciting, magical, experience – you go down a dark alleyway and there’s a code, and you open the door and, magic! A really cool, well-designed apartment in a country you’ve never been to.

I would frame that darkness you talk about as a kind of gravity, we don’t take these things seriously unless there’s something on the line. I just hope we’re forward-looking and data-driven enough now that we can imagine some of the potential outcomes and cut them off before we have to experience them. I hope that that’s the cultural change that we’ll go through as a society, as a result of all of this.

I really want the technologies we’re building to be a force for good and we do have that opportunity. And, to some level, that responsibility. Arm is one of the companies behind 2030 Vision, a matchmaking website between organisations working towards the UN Global Goals and technology companies. Anyone reading this – come and get matched up so we can build some cool things. That’s one way for people to come together and innovate for something bigger and better than just profit or entertainment.